| hosted by Joseph Kim

| hosted by Joseph KimAlthough people dealing with rare diseases may be few, they all share a common humanity with the broader population that must be considered when designing trials.

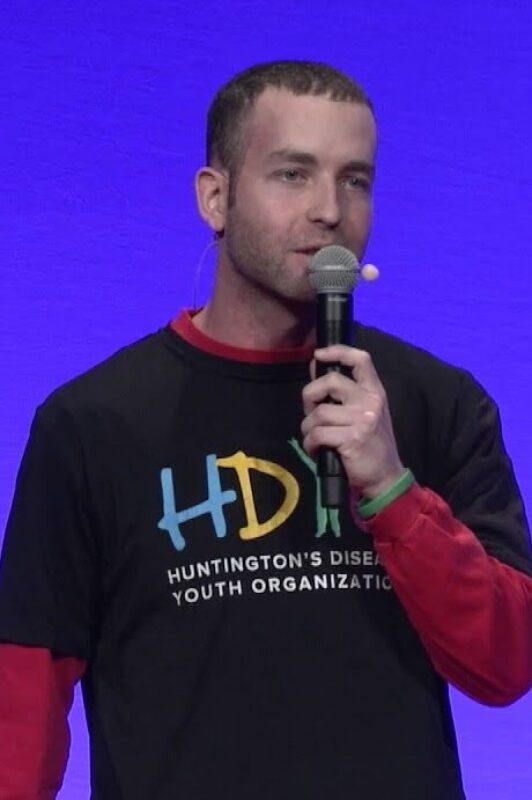

In this episode, Seth Rotberg, co-founder of Our Odyssey, shares his family and personal journey with Huntington’s disease and his take on how clinical research could evolve to improve the whole experience of the patient community with this rare disease. He shares the story of his mother’s misdiagnosis, the impact on his life and how he later discovered he was a disease carrier, and how that motivated him to advocate for the rare disease community. Seth discusses how the clinical research space can repair its reputation by taking the whole person into account, emphasizing the need to improve communication with patients, understand their needs throughout the participation, and return data to create a trusting relationship with the entire community.

Tune in to learn more about the roller coaster Seth has gone through and the lessons he is sharing from his ride!

Seth is more than just a patient advocate – he helps make a difference in the community by immersing himself in the patient’s perspective. His passion is driven by his mother’s 17-year battle with Huntington’s Disease (HD). His health journey has provided many years of hands-on experience in fundraising, patient advocacy, volunteering, B2C content, strategic planning, event planning, and program management.

Seth loves to connect with people and build relationships across all stakeholders within the health space; ranging from life science companies to local patient advocacy organizations. He resides in Chicago, IL where you can find him running, playing or watching sports (especially the Boston Celtics), hanging out with friends, reading, or volunteering for the nonprofit he co-founded, Our Odyssey.

Research Confidential_Seth Rotberg: this mp3 audio file was automatically transcribed by Sonix with the best speech-to-text algorithms. This transcript may contain errors.

Joseph Kim:

Welcome to Clinical Research Confidential! On this show, we highlight and demystify the inner workings of this greatly misunderstood activity called clinical research. Now, why is clinical research important? Well, it’s the basis for nearly every modern remedy for sickness and a growing method to build trust and solutions meant to optimize health. But it’s not for the faint of heart. And so on this show, you’ll hear what it really takes to succeed in the clinical research game. I’m your host, Joseph Kim, and I’ve spent over 23 years in the clinical research industry, now serving as the chief strategy officer for ProofPilot. Get ready for some adventures as we look into the underbelly of clinical research.

Joseph Kim:

So I’m really excited to be here on Research Confidential today with a world-famous patient advocate, Seth Rotberg. Seth, welcome to the show.

Seth Rotberg:

Thanks, I appreciate you having me here, and excited to dive into my own story, but also just have a fun conversation with you about healthcare space and clinical research.

Joseph Kim:

Yeah, for sure. Your story is pretty unique. I mean, first of all, your mother was diagnosed with Huntington’s disease and then you found out through genetic testing that you’re a carrier for that as well. Tell us a little bit about that story around learning about that, about your mother, and then about yourself. Tell us about the emotional roller coaster through that.

Seth Rotberg:

It was certainly a roller coaster. That’s a great way to put it, because you never know, sometimes with those roller coasters, you think you’re ready for that drop and then you go up and up and up and you’re like, wait, wait, we’re going higher, right? It’s like going on that Superman ride on Six Flags, and you’re like, oh, I can do this, and you’re like, holy crap, I got to hold on because it’s going to be a long, long ride. And that’s kind of how I felt with learning about my mom’s diagnosis, because in the rare disease space, there’s an average lifespan of being misdiagnosed for anywhere from 7 to 10 years to even 15 years, and she was misdiagnosed for probably the first 5 to 7 years. Doctors said she had major depression because she was always just upset and we weren’t sure if it was just her being upset because her mom passed and she was very close with her mom and going through that grief and loss, it’s always challenging. But then there’s these mood swings, and then we also noticed she had like poor balance and wobbly movements, slurred speech, and we knew she wasn’t like a heavy drinker, but we had neighbors who were like, oh, maybe she’s drinking, she’s, you know, she’s boozing, as they would say back in the day.

Joseph Kim:

And how old were you at this point?

Seth Rotberg:

I was like 12 or 13 when we started noticing it more and more, and then, yeah, I mean, you know, being a middle school kid and then going into high school and still dealing with this while trying to fit in with your peers, right? You’re trying to make a new name for yourself when you go into high school, and unfortunately, with high school kids, we can all admit it, you want to fit in, but it’s also can be a little like judgy, right? Like you feel like you might be judged right away. And so eventually my family and I, we had an intervention with my mom because it got to the point where it’s just too chaotic at my house, where my dad and I were thinking about just leaving and saying, we can’t do this anymore. Yeah, I mean, it was tough, and my older sister, you know, she dealt with it too, and she eventually went, moved to go to school out in Arizona. I’m originally from Boston or outside of Boston, I should say, and she hated the winter, so I don’t blame her, she’s like, get me out of here. But, you know, she was able to, while she was in college, right? This is, kept going on and on, and so we had this intervention, we checked her into a mental facility to get all these tests and evaluations done. And I think what was tough was seeing your parent, your loved one in a facility like that, especially when I was like, oh, she doesn’t belong there, like, let’s figure this out quick, and then that’s when the doctors told my parents, oh, it’s Huntington’s disease in your family? There’s usually family history. And so it was all new to us, my mom, that’s when she was officially diagnosed, you know.

Joseph Kim:

And was that a relief to know it was that or versus something psychiatric?

Seth Rotberg:

I think it was just kind of a lot to process, right? Because we’re like, what is this? What is Huntington’s disease? What is this condition without a cure? And so I think we were all trying to process and figure it out, and of course, it’s a lot more prevalent now. But like, you know, I went to Google and searching it and you see the symptoms of like mood swings and wobbly movements and lack of concentration and all these symptoms. I was like, oh, my mom has all these like, this makes sense. But I was 15 at the time and I was definitely in denial because I was like, man, this sucks. Like, I have to now adjust my lifestyle, and seeing my friends’ parents, they seemed kind of normal, like, my mom’s different. And so I felt like it was challenging to just kind of be out in public with my mom, because again, those physical symptoms were noticeable and I was too nervous and scared to like say anything about it. So I was like, I don’t want to be out in public because it’s embarrassing because people are giving her weird stares or having friends over. So I would even like try to stay at my friend’s houses overnight. I remember in high school, just like kind of feel that sense of normalcy again and it was challenging. I was an angry high school kid trying to deal with that and trying to deal with like the ins and outs of being a high school student, and so it wasn’t until I went to college realizing I’m at risk and I have a 50-50 chance of inheriting this disease. And I think what hit me was like, I would forget an earlier conversation or drop my phone, and it just reminded me of my mom. So let me look more into this. And so when I looked and realized I was at risk, I thought I was like, maybe I should go through testing and see do I have the same condition? And when I was a freshman, I was thinking about it. I spoke to my sister and my aunt about it and I was like, I’m not ready, but what’s challenging about this is not that physical piece, but the mental piece, right, of do I have this, do I not? How is this going to impact my future when it comes to getting married, having a wife, kids, career, right, a house? All these things that I think a lot of us, I guess I’ll speak for myself, really want in life is like, you know, I want to have that future. I want to have a happy life. And when I see my mom, I’m like, okay, she’s slowly deteriorating, both physically and mentally, is that going to be me, too? And so I just was like, I’m ready to test at the age of 20, I went through this process very quickly. It was like a two-week turnaround where most of the time it should be like anywhere from 2 to 4 months because you usually see a genetic counselor and you make sure that you’re mentally prepared for that answer, because even if you test negative, people do have that survivor’s guilt, right? If they have a sibling who might get it and they’re like, man, I’d rather deal with it to my brother or sister. And so at the age of 20, I found out I have the disease. It’s a little complicated because people use the term, oh, you’re diagnosed. But technically I’m not diagnosed, and so then they’re like, oh, so you have a chance of not getting it. I’m like, no, I’m guaranteed to get it, right? So it gets confusing because I am a gene carrier, but like I’m pre-symptomatic or pre-manifest to inheriting it, but because of research now there is data out there that states that there’s changes that happen anywhere from 15 plus years prior to being clinically diagnosed. And so as we speak, I’m sure there’s changes happening in my brain slowly but surely. And so that’s where I’ve decided to become more of an advocate, not just for me, but for others in the Huntington’s disease community and in the larger, rare disease community and health community. Because when you learn about a health condition, it’s very isolating, you feel like no one understands you. And then once you meet that one other person, you feel like you can just be yourself again and you can just, they get it, they understand what you’re going through.

Joseph Kim:

Yeah, so, you know, after the anvil dropped on your head, like, oh, you’re a carrier. How much did, at the time, there wasn’t like, oh, now take this pill, right? How hard was it to navigate both like, what were your options today versus, is there a research I could get into, or was research not even like in your brain because that’s not you weren’t studying that, right? I think you were studying economics or something like that. So clinical research isn’t something that you pull out of your back pocket. How many choices?

Seth Rotberg:

Yeah, that was like the last thing. It was kind of like, Let’s do a fundraiser. I’m a big basketball fan, so I was putting on like a … through basketball charity event, that was pretty fun to do. And then, like, just trying to share, share my story or even just my mom’s story of trying to raise awareness because it took me a few years, even after testing positive, to like, be more publicly open about my story. And so once that happened, I was like, all right, like, this is great. I can join these local and national nonprofit boards to really help make a difference and help other people out. But it wasn’t until actually, like the research side of things came somewhat more recently where, in 2018, I did a TEDx talk on my story in my hometown. I was like, wow, the power of storytelling is remarkable, because I specifically remember, I’ll never forget, after the Talk, there’s like a lunch break, and I was talking with a few of the people from the audience, and one person just came up and said, hey, thanks for sharing your story. Like, yeah, of course. He’s like, no, no, like, really, like I, I deal with a different health condition, but I want to now share my story too, and I want to help really make a difference. And those little things are always going to stay with me because I’m like, okay, my story actually means something to someone out there who’s willing to listen and know, hey, I’m not alone in this either, and I can also share my story to not only create awareness but make a difference. And so then I was like, I want to work in healthcare. I want to understand more about the ins and outs of drug development and how challenging it is. And that’s where I kind of took that leap to join the healthcare space professionally and not just be like, hey, I’m a volunteer for my local community, but hey, I want to be a professional in this and help make a difference. And that’s also when I learned about, one, how challenging science is and how difficult it is to bring a potential treatment to market, but also some of the, I would say, challenges that are, I, in, personally, that I think we can improve on that I feel like we still don’t improve on because of how things are structured in the healthcare space. And just to give an example of that patient perspective earlier in drug development, how to manage those expectations with the community to say, hey, this is a potential treatment, it may or may not work because I’ve heard so many times in my community and I get it, it’s, hey, here’s the cure, here’s the cure, here’s the cure, and then when it, drug doesn’t seem to meet its endpoints or it doesn’t work out, everyone loses hope. And you’re like, damn, that’s stinks. Where I’m like, okay, like, this might work, but how do we educate patients on what it means to go from a phase one, you know, to phase two to a phase three, to say, hey, there’s still a chance that this may or may not work, but also, what do you guys willing to risk to participate in a study? What are you willing to benefit from? And how do we make sure that your voice is being heard, even with the trial design, the protocol, so it’s not too burdensome? What are the things that you guys need? Because otherwise how I see it is when it gets to that recruitment part of it, we’re looking for that perfect patient, which I might have shared with this previously with you, but it’s always the analogy of, I always say the dating apps where you keep swiping like, oh, I found that, oh this person could be a good fit. And then they might be a good fit, but then after you kind of do, and I’ll kind of compare the two, right, after you meet them once, it’s kind of like that first screening visit or that pre-qualifier for the study, actually, it’s not a good fit and then you’re back to square one. And I think that’s the challenge, is like we’re trying to find the perfect patient at times because yes, you want to meet your primary endpoints of what you’re trying to look for and see, are there improvements? But if you allow other patients in it, I think it’s going to make it easier not only to recruit, but then also easier to see if your treatment might potentially work or not.

Joseph Kim:

Yeah, I mean, there’s a ton to unpack after what you just said here. So like, let’s talk about a couple of things. Like first of all, the idea of a cure, right? That’s actually such an old word. We all use it, I use it too, like the cure for cancer, cure for, but, you know, certain things can’t be, quote-unquote, cured because they’re genetic, but there can be symptom abatement or improvement in certain functions. So I can totally understand why when a drug doesn’t meet its endpoints, why you think like all hope is lost. But, you know, many diseases, including oncology and neurodegen and these heavyweight ones, progress is always made kind of incrementally through research. And I’m glad that you’ve joined our community and research because we need folks like you, and more than that, you’re actually an employee of Citeline, which is a partner of ProofPilot. So why that’s really important to me is because for too long sponsors, the industry, healthcare, have used patients, and I mean Used with a capital u, as just like inspiration stories that are unpaid or input that’s unpaid. So the fact that you’re on the payroll as a working taxpaying employee of Citeline, I think, speaks volumes to that company and the impact you can make for sure.

Seth Rotberg:

Yeah, no, I mean, I think you’re right, is, sometimes patients or I guess how they say it, subjects, which is a whole another thing I’m like, how do we change that? Like, imagine if you start calling people subjects, you’re like, oh, that doesn’t, that sounds degrading. Like, let’s just change it to patients. But I think we’re not just data points, right? We’re human beings behind that data point. And yes, it’s exciting when you see positive changes in your data, but you’ve got to understand that there’s people willing to sacrifice part of their life to participate. Whether your drug works or not, they need to be, one, understanding that, but also communicating that no matter what happens, because I’ve seen the great companies out there who right away when they, you know, you see on an update that a drug is not working or it’s halting because of adverse events or whatnot, and they communicate right away to the patients participating. I’ve also seen where and I’ve had friends in studies where, unfortunately, they heard the news through the press release and the company didn’t reach out to them until three days, four days later.

Joseph Kim:

I’ll tell an investor before a patient, which is kind of crazy.

Seth Rotberg:

And I get it because of like the stock market and all that, but like, my thought is you should always have that pre-approved, like communication language ready to go if that ever happens in your situation or in your company so that way it’s easy just to push out all at once, but it’s challenging. I think some companies are improving it when it comes to that patient perspective earlier and throughout drug development, I think it’s, it’s all about just including us, because without that patient, you don’t have a study. Without that patient, you’re not going to be able to find a treatment, and I think that’s something that, to be honest, frustrates me because I’m like, we should be at the table with you guys. I get it, when it comes to companies with their legal and compliance, like, oh, it might look bad for us. I’m like, dude, it’s not going to look bad unless you’re like paying them under the table and saying, oh, thanks for saying that for us, thanks for saying that, right? But if you understand that there’s people out there, like myself who are like, hey, I get it, from both the business side and the community side, let’s work together, let’s figure out how I can support you, it’s going to be a lot more successful. And I’ve had companies I’ve spoken with in the Huntington’s, that’s working in Huntington’s disease, and they’re very receptive. And I’m like, those are the people I want to be working with or like staying in touch with, not the ones that are like, thanks, Seth, like, I’ll get back to you in six months. And then when I look and I’m like, how’s your recruiting going? Like, we don’t know what to do. Why aren’t patients coming to us? I’m like, I don’t know, maybe because you’re asking them to come in twice a month and you just didn’t ask them what they’re looking for?

Joseph Kim:

Yeah, I mean, there’s two companies that come to mind, there’s probably a handful of others, but like Lilly and AstraZeneca, I think work with patients, actually compensate them for their expertise and time in an above-the-board way, so it’s happening, but it’s not happening enough, to your point. Let’s talk about this idea of participation because you just touched on it now, like coming in twice a month. Is it fair to say that if you take a patient with a certain condition and their timeline of activities might look like something they do with a doctor two or three times a year, something they do sort of daily, and that’s it, compared to when you ask them to join research, it’s an exponential increase in what you’re now asking them to do, it’s like a huge behavior change? Is that the right way to think about it?

Seth Rotberg:

I would say so. I mean, you also have to think about, let’s talk about my own example, right? So I participate once a year in an observational study, which is awesome and I enjoy it. Challenge is that one time in that year is when they’re going to try to see how I’m doing, but what about the other 11 months of that year, right, and the changes that are happening? And whenever I go into that study, it’s like a couple of days leading up and then even that day I start to feel anxious because I’m like, I know the questions that they’re going to ask me, right? Like there’s these different cognitive tests of naming every animal that begins with the letter A and whatnot. I’m like, oh, I got to do, and I’m competitive, so I’m like I’ve got to do better than last time. And so then if I’m like, oh, I don’t feel like I’m on point, oh, is it because I didn’t have enough coffee or because I’m having a stressful week with life, or whatever the case might be, but they don’t know that. So then it’s like they’re now grading me based off of this one-time experience versus how can I also then play a part and say, well, yeah, the last couple of weeks have been stressful because of X, Y, and Z, so that’s why maybe things are different. Or I participated in a virtual one where it’s doing these cognitive tests on a computer after an eight-day workweek. Well, think about it, if you’re staring at a screen for 8 hours and then doing three more hours of cognitive work, your brain’s fried, so you’re not going to be on point as much as you might be if it was like first thing in the morning. So these things actually play a huge role, and so I always just think there’s opportunities to hear feedback, not just that one or twice a year office visit, but share more about it. Maybe you have a, you recommend having them journal things or write things down whenever they notice something good and bad. Because again, I think it’s tough to measure when it’s just that one time of year. And then the other kind of part I wanted to mention is like just participating in a study, right, it’s, as a patient, it’s like, what questions are you supposed to ask the site? For me, I work full-time, so how many times do I have to come in? How many hours per visit? Do you guys offer weekends? Do you offer a workspace in between meeting with different doctors so I can continue to do work, right? Do you guys have an open-label extension? Is that in the protocol? Will I be approved for that? If you have that piece of it, right? These are things I didn’t even know about until just talking with my other friends and colleagues in the healthcare space to be like, hey, these are questions you might want to ask. Or like, what do you guys cover for your expenses? Don’t get me wrong, like an honorarium is nice, but some people are like, hey, can you actually cover my therapist for me? Because this is going to be tough for me to participate in the study and I don’t have access to a therapist, and that’s actually what I want over the honorarium. But it’s like unless you ask these things, I feel like it’s just, it’s very tough to know what’s going to be best for the patient.

Joseph Kim:

So what I’m hearing is like, this idea of zero expectations in a bad way, like patients aren’t really sure what’s coming at them, and they want to make sure that the tradeoff of participating makes sense for them financially, emotionally, medically, and not having that roadmap into what’s going to happen and maybe different things that they could tweak to make their participation better just aren’t put forth to them, is that right?

Seth Rotberg:

Yeah, absolutely, I mean, and don’t get me wrong, you know, whether you’re dealing with a chronic condition or rare disease or cancer, right? Like you’re willing to do whatever it takes to get into that study. And I’m going to speak more in the rare disease space, right? That could be the only study. So you’re willing to travel across the country for it? Probably. But the other thing that I think, and I’ve learned this, is like, again, it goes back to managing expectations and saying, hey, this is a big commitment. Are you willing to make this commitment to participate? Because if you drop out, it doesn’t work where the next person can just jump into the study, and that actually impacts the results of the study. And I think that’s something also important to share is like, at the end of the day, these companies are also taking a risk to see if this works, and we know what 80 to 90% of trials end up failing for a variety of reasons, and so it’s not like a pharmaceutical biotech company gets like a rebate or a refund on their investment, and so it does impact all of us. I think it’s interesting when I see the business side, because I understand that like, it’s essentially a product, a potential service, but because it involves human beings, that’s where people are like the whole political piece of it that we won’t get into, but of like, oh, they’re in it just for the money and stuff. And I’m like, but if they don’t have a treatment, there is no money, right? You know, like if these trials are failing and they’re costing millions of billions of dollars, where else are they going to get it? They’re a business just like anything else. But again, that’s just my perspective because of what I’ve learned about the ins and outs of it. Can there be improvements? Absolutely. But again, there has to be communication with all the stakeholders in order to make that happen.

Joseph Kim:

Let’s talk about one other big topic here before our time is up, and this is the idea of data return. It’s a personal failure I’ve accepted and I have it mounted on my wall, like Joe has failed in returning data back to research participants, and a lot of us in the industry have promoted this idea and tried to pat ourselves on the back for very incremental improvements, but I don’t see anyone doing that at scale as a routine to return individual data back to a research participant. Now, this might just only be the endpoint, or how about the drug that they were taking? Vitals labs, …, right? It’s nothing that crazy. Do you see anyone doing that? How important is that to patients? Educate me here.

Seth Rotberg:

I haven’t seen much of it either. I think it is important to patients, depending on what they’re willing to learn and understand, but I also think that data should be shared with other companies that are trying to do the same exact thing, because then let’s not reinvent the wheel, right? Like, hey, if this doesn’t work, well then, share the data and share what your findings were so that others don’t make that same mistake, because at the end of the day, most likely that company is not going to go back into that same disease state because of the study not meeting at ten points. But other companies that are trying to work in it might say, oh, thanks for sharing that, right? Now from a patient side of things. I participated years ago in an exercise study and it was really cool and I asked for the results and I never heard anything about it. And so to me, I’m kind of like, well, what did you guys find anything? Like, even if it’s not good news, I’d rather understand the benefits. I know the benefits of that exercise helps, but was there anything fascinating that you found that, hey, actually, if you do exercise for 45 minutes instead of 25 minutes, it’s, actually does make a huge difference? So I do think it’s essential, it’s important, or even if they do a publication, is there an opportunity to, like, share it back to the participants? Yes. How they go about that, I think personally, it could be a logistical nightmare because they’re trying to find those patients again, that could have been a year later they did a publication and they’re like, how do we make sure we get in contact with the patients? Because the other challenge that you and I both know is like, at the site level, they’re dealing with multiple studies all the time, and so it’s like, how do you make sure that’s easy on the sites to then, literally, just like forward the email or forward the publication to those patients anonymously or put it in their portal so that they can say, hey, here’s the results, here’s what we learned about the study you participated in.

Joseph Kim:

Right. Or even just take it out of the sites’ hands, like don’t burden them with that. Let them know it’s happening and then have a third party be able to connect those dots responsibly.

Seth Rotberg:

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I think data is essential. It’s how we learn more about the ins and outs of just the human life. And I think there could be better ways to share this news and information to patients so that they do understand, hey, maybe this didn’t work out, but at least I learned a little bit more about my own condition or my own bloodwork or whatnot, if there is something.

Joseph Kim:

I mean, I always imagine this conversation. Let’s say you were just finishing your part in a study and I’m asking you like, hey, Seth, how did it go? Did you ever find out what you’re taking? And you’ll say, I don’t know. And what about your bloodwork or your like, your endpoints? I don’t know. That doesn’t really inspire me to join clinical research, right? This is something, I think, very small that the industry can do. If you just armed volunteers who are leaving with their data at some point, the next conversation they have is going to be way more positive to the un-indoctrinated if they want to think about doing a study. We complain that nobody cares about research. Well, we can’t expect people to care about research if we don’t care about those people in research, I think.

Seth Rotberg:

Absolutely, and one last point I will say is the power of hearing other people’s experiences, just like you said. And I think it’s so important because when you hear that experience from someone else in your community and they’re saying, oh yeah, this is what I’m participating in, you’re more likely be like, I want to learn more about that too. So another observational study I did participate in, and I was, you know, a study out in Wisconsin and I shared it with the community. I said, hey, this is a study. They’re looking for patients. I participated, here’s an update from me. Here’s a picture of me doing a spinal tap, because I was always people like, oh, a spinal tap, like big myth, it’s scary. I’m like, It’s not that bad, I promise, and you get a great breakfast after it, so you’re good. But once doing that, then suddenly, I see other people posting about it in the community saying, oh, I’m participating, this is awesome. Like, thanks, Seth, for sharing. And so it’s like the ripple effect, I think, of understanding these studies and being able to share your experience. And I think it is challenging because again, if you have a placebo and people start sharing, then you’re like, wait a second, I’m not feeling like that. So I do get that part of it, but sometimes there has to be a way to encourage people to share with someone because then they feel good about it, right? They feel good about, hey, this is an update, like I survived the spinal tap, right? Like even just saying that or, hey, like I’m feeling great. People love to share these things because it gives them a little bit more hope and courage as well. And so I don’t know how to figure that out because, as I’m saying it, I’m like, Well, if there’s a placebo and then people figure out who’s on drug or who’s not, that could impact the results. But if there is a way to make it so that people were able to share with someone, right, of their update, even if it’s like, hey, site, I wanted to tell you how I’m feeling.

Joseph Kim:

Yeah, I mean, it is tricky with science because you want to make sure that data is being captured and analyzed, and when data starts leaking out into these other directions or being unsolicited. But I think there’s some good ways around it, right? When we talk about community, I think, which is the big, it all falls under this idea of community, it doesn’t always have to be free-flowing interaction. So if you think about like the traffic app, Waze, that’s a community, right? But it’s anonymous and you’re not doing a ton of stuff, but you all rely on each other to say the accident’s not there anymore, right? So there’s a way I think we can do anonymously with technology to create a community to help people feel like they’re not alone and to help people help other participants in a very responsible way that doesn’t destroy the science to your point. And, you know, these are things actually we’re working on too and we’d love to partner and make that happen in the future.

Seth Rotberg:

Yeah, I think anonymous is, honestly, I think it’s the way to go. My first connection with people in the Huntington’s disease space was AOL Chat room when you had the anonymous chat rooms, right? And I’m like, this is awesome, because at first I’m like, okay, I just want to listen. I’m kind of like what they call a lurker, right? I just want to see what other, if I relate. And then it’s kind of like, okay, now I’m going to chime in a little bit. Okay, now I’m going to lead the conversation. And I think that’s kind of the big piece is like, if you’re anonymous, it’s up to you on how much you want to share versus, you know, the Facebook groups are great, but your name is behind it, so anything you do share, and like I think the groups are fine, but personally, right, my dad, sister, aunts, uncles, cousins, right, they’re on Facebook, if they’re in the group too, it doesn’t feel as natural to me, right? Because I love them to death, but sometimes I just need my own space too to kind of share this thing.

Joseph Kim:

Final question. What’s really the driver behind patients wanting to stay or drop out of research, outside of whether the drug is working or not, right? So one of the number one reasons is the drug works or doesn’t work or it’s making nauseous or not, right? So let’s take that out. Aside from lack of efficacy and AEs, what really drives patients to stay in research or drop out?

Seth Rotberg:

The dropout one is probably easier to answer, unfortunately, but probably I think it’s too burdensome on them, right? Too many visits or the reimbursements aren’t there or they don’t, when we think about also just diversity and inclusion, right? We’re trying to get different people involved, whether it’s their age, gender, socioeconomic background, ethnicity, we have to meet them where they are, and I think if you can cover these costs upfront, that can also maybe allow people to participate. But I think the challenge is just the burdensome piece of it, of like, hey, this is a lot for me to do, and I didn’t realize it ahead of time because maybe I wasn’t educated enough or I just was like, hey, this sounds like a good option, or my doctor said this would be good, not knowing all the ins and outs of how many study visits and whatnot. What keeps people in it, I think is great communication with the site, being able to be flexible with that patient’s schedule, right, and the ability to, again, meet them where they are saying, oh, you’re busy this week, but what about on Monday? Monday, does Monday work? Morning, or what works best for you? Because when it turns to what works best for the site, that’s where you’re going to start going the wrong direction. And so I think the communication and more importantly, making them feel like they’re a part of the study, and that speaking, thanks Seth, for joining. A simple Thank You goes such a long way. I got a card from someone saying thank you for participating and I’m like, this is the best thing I’ve done, like, this is awesome. Imagine, like, after each visit, just getting a card from the site or a quick email, hey, thank you again for today, I hope you and your family have a great weekend, right? Build that relationship, build up the trust because then they’re willing to feel like a part of that study and a part of that larger puzzle.

Joseph Kim:

Yeah, at ProofPilot we like to try and use technology to remove all the sort of, the manual things you can systematize to allow the individuals to focus on that relationship, right? So the study coordinator is another big reason why lots of patients stay in research. So we’re trying to take some burden off the study coordinators in trying to navigate the technology and the study so they can just like look the patient in the eye and start to have that conversation. The study coordinators I’ve talked to, love the visits with the patients and the patients love them. There’s just that human connection, that’s also a big reason to your point of why people stay in, because there’s that level of trust and communication and relationship that just can’t be replaced with a bot or some faceless app that doesn’t have a person behind it.

Seth Rotberg:

Yeah, and you know, the last thing I’ll say is just checking in with the patients, right? Like, sometimes I get it. You’re on a schedule, you want to try to get all the patients in and throughout the study, but being able just to simply just say, how are you doing? How is your day going? How’s your week going? You know, because then it removes just like the professional side of like, hey, I know you’re here for the study, but I also want to see how you’re doing as a person, as a human. And I just, I think, go such a long way. I mean, I have my, I’ll say my favorite neurologist in Huntington’s disease and like, you know, he’s my mom’s neurologist, and I’ve seen him and whatnot just to check-in. But I also know, like, I can go to him, just say, hey, can we just chat, check in? He’s like, absolutely. And it’s those people that you want in your corner that are going to be like, hey, I’m willing to dedicate that time and like build that relationship up, because at the end of the day, it’s a two-way street. It’s not just, hey, this is what I need from the patient every time, but the patient needs, again, that mental health services, or hey, do you guys have a social worker on site that I can speak with or anything else? Then you feel like, hey, okay, we’re doing this together. It’s not just a one-man team or one-woman team.

Joseph Kim:

Yeah, I love that. On that note, Seth, thanks so much for spending time with us. Keep fighting the fight personally and professionally. I continue to look forward to your progress as a patient advocate as well as a valued member of the Citeline team. I think you guys are doing some great stuff there. Thanks again for joining us and have a great day.

Seth Rotberg:

Thanks, I appreciate it a lot, and have a good day as well.

Joseph Kim:

Thanks.

Joseph Kim:

Thank you for tuning into Research Confidential. We hope you enjoyed today’s episode. For more information about us, show notes, transcripts, and resources, please visit ProofPilot.com. If you’d like to debunk a clinical research myth, share some war stories, or maybe just show our audience what kind of heroics it takes to pull off gold-standard research, send us your thoughts, episode ideas, and more to help@ProofPilot.com. This show was presented by ProofPilot and is powered by Outcomes Rocket.

Sonix has many features that you’d love including upload many different filetypes, automatic transcription software, automated translation, secure transcription and file storage, and easily transcribe your Zoom meetings. Try Sonix for free today.